One of the hottest new trends in architecture has actually been around for centuries, and it could be a key strategy for making wooden structures more fire resistant. “Shou sugi ban” roughly translates to “burnt cedar board” in Japanese, and it was developed by carpenters seeking a unique finish that would improve the durability of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica).

Commonplace in Japan since the 1700s or possibly even earlier, the technique traditionally involves strapping boards together and creating a fire in between them, which is allowed to burn just long enough to char the surface of the boards before it’s extinguished with water, buffed with a wire brush and sealed with a plant-based oil like tung. This produces a hard shell on the wood that naturally protects the rest of the board.

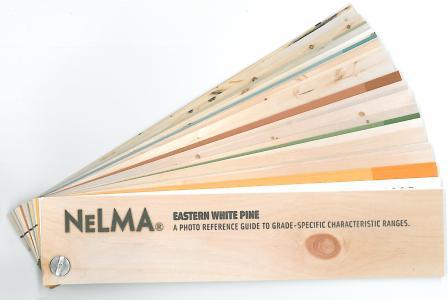

These days, the same effect is typically accomplished with a blowtorch, especially in the United States and Europe where it’s exploded in popularity thanks to its dramatic look and eco-friendly nature. The process chars the wood to varying degrees, depending on the desired outcome, ranging from a light toasting to a blackened “alligator skin” texture. A darker char provides the greatest benefits. Interestingly, the technique can be used on all kinds of wood, including Eastern White Pine.

When we wrote about this previously, lots of our readers wondered how such a process could possibly make wood more resistant to water, insect damage and especially fire. Nakamoto Forestry, a Japanese company with a shop in Portland, Oregon, inadvertently tested out the latter when last year’s Tubbs Fire burned around a house clad in its shou sugi ban siding just outside of Calistoga, California. The fire came right up to the side of the house, but the only damage it sustained was melting of the resin the company used on the back sides of the planks to hold and fill loose knots. They’e explained a little bit of the science behind how this works:

The two main components in softwood lumber are carbohydrates, like cellulose and hemicellulose, which make up 65-90% of the non-water mass, and lignin, which makes up the other 10-35%. Cellulose is made of a linked chain of glucose molecules, or sugar. Hemicellulose is also made of sugar, but in addition to glucose, it’s made with a range of different polysaccharides. Lignin doesn’t contain any sugars and is the main rigid, structural component of wood. The basic premise of heat-treated wood longevity is that the carbohydrate portion is burned off, leaving the structural lignin, and therefore depriving fungi and wood-eating insects of what they metabolize to survive.

In addition to being insect and microbe food (as well as hygroscopic), those carbohydrates are also fuel for fire to consume. In order for wood to ignite, its temperature must be high enough that pyrolysis takes place and the chemical reactions of combustion start. Ignitability of wood is dependent on the thermal properties of the species, moisture content and dimension of the piece, and the way heat is applied to the material.

The factors affecting the ignition of wood are generally well known: wet wood is more difficult to ignite than dry, thin kindling ignites more easily than thick logs, and softwood species ignite at a lower temperature than hardwood. Less common knowledge is that wood burns in stages. Cellulose is the first component of wood to ignite and it burns away quickly, leaving mostly lignin and other sugars behind, which become charcoal. Charcoal is the last component of wood to burn, as it requires higher temperatures than cellulose to ignite. This is the key to why shou sugi ban is naturally flame resistant: the cellulose has already been burned away, leaving a surface that requires much more extreme heat than non-heat-treated cypress to ignite.

Shou sugi ban is particularly well-suited for cedar and cypress, but produces similar effects on other woods as well (including pine!), though it becomes a bit of a misnomer in this case and proponents of the technique prefer to use names like “shou piney ban” to differentiate it. Many architects are beginning to experiment with using charred pine as a durable exterior siding, like the Charred Cabin by Del Rio Arquitectos Asociados pictured at the top of this page. Since the process can be quite time consuming for builders, some lumber providers have begun offering pre-charred siding to consumers.

Particularly in the American West, designing architecture that can withstand the danger of frequent wildfires has become a greater concern. It will be interesting to see how architects continue to experiment with this material, and whether it could play into new fire resistance strategies in the near future. If you test it out with pine, please be sure to let us know!