Rosewood, mahogany, ipe, 800-year-old cedar: there’s no doubt that these tropical species and old-growth trees found deep within protected forests can produce beautiful wood products, but at what cost? Customers might only be thinking of the gleaming floors that will soon be installed in their homes when they purchase ‘exotic’ lumber products, but despite the 2008 passage of a law aimed at reducing U.S. imports of products from illegal logging, the problem hasn’t disappeared, and the effects can be devastating.

A two-year investigation by Global Witness, an international non-profit, found that U.S. customers are unknowingly purchasing illegally logged products from Papua New Guinea’s tropical forests, revealing that companies aren’t doing enough to ensure the legality of what they’re selling.

Papua New Guinea is home to the world’s third-largest tropical rainforest, and more than eight million acres of its land has been leased to foreign interests that illegally harvest old-growth trees on indigenous territory, where forests are protected. Approximately 8.2 million cubic yards of tuan wood, also known as Pacific mahogany, was illegally clear-cut between 2009 and 2016.

China, the world’s top furniture and flooring maker, is one of those foreign interests, and funnels a lot of that illegal wood into its own manufacturing. It then sells these products to large retailers around the world, including the United States. In April 2017, Global Witness informed ten U.S. companies about the findings in its report, but not all of them responded or took action. (The Home Depot has taken taun wood off its shelves.)

Of course, the Amazon is another troubling source of illegally logged wood, where rampant, unchecked clear cutting destroys the forests that have been home to indigenous tribes for many generations. Again, it’s almost impossible to tell whether species like Brazilian Ipe were logged legitimately or not, and the resulting products are sold all over the world. Customers in the United States may have no idea that their contractors are using wood violently torn from indigenous land in Peru, for example.

The problem lies in the traceability of imported wood. Many companies don’t go far enough to verify the legitimacy of their supply chain, and even when they do, illegal operations can be convincingly camouflaged. While the Lacey Act has definitely reduced illegal imports in the United States, cases like Lumber Liquidator’s 2016 sentencing for illegally importing hardwood from forests that are home to endangered species prove that it still happens. And Canada has its own problems, particularly with old growth cedar.

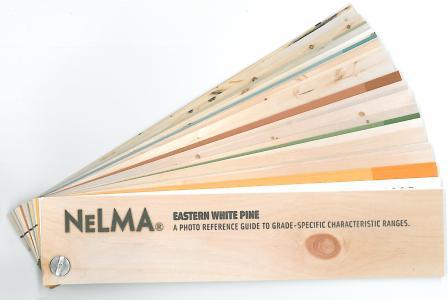

So what’s to be done about it? Perhaps the biggest step builders, contractors and consumers can take to help is choosing wood products that have been sustainably grown and harvested within the United States. Not all logging operations in the U.S. are equal in their efforts to protect the environment, and it’s important to seek out wood products certified by third party organizations like the Sustainable Forestry Initiative. But with domestic wood – and maybe even wood grown practically right in your own backyard, like Eastern White Pine – there’s a lot less opportunity for obfuscation.

Read more about how sustainable forestry differs from conventional forestry in the United States, how working forests support rural families, and why sustainable forestry is crucial to the future of wood.

Top photo: Signs of illegal logging in the Mt. Cagua area of the Philippines, via Wikimedia Creative Commons/RMB.