The tax on tea was not the only issue that raised anger among American colonists in the 1700’s. Eastern White Pine played an equally key role in events that led to the Revolutionary War and American Independence  from England.

from England.

The majestic Eastern White Pine is the tallest of the pine species in North America, basically the Sequoia of the Northeast. Trees 150 to 240 feet tall and trunks free of branches to heights of 80 feet or more were plentiful when the “New World” was being colonized by the England and other Europeans. The tallest known height recorded was a 250′ Eastern White Pine tree noted in a 1760 publication by William Douglass.

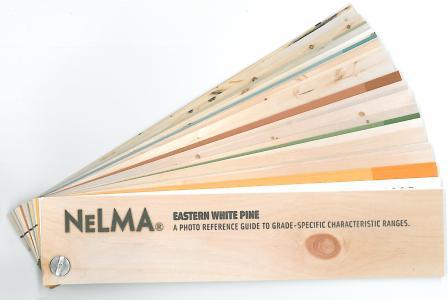

Lumber from these trees was very light, yet strong. The woodworking properties of the species made it an extremely versatile wood, very easy for a builder to cut, shape and finish. In addition, its organic characteristics and slow growth created a fairly high decay-resistant material. With these qualities and its abundance, the colonists built just about everything out of Eastern White Pine…their homes, businesses, bridges and countless other structures, along with day-to-day items such as furniture.

The colonists immediately discovered that the tall, straight Eastern White Pine was the perfect material for shipbuilding, particularly as masts for large vessels. English explorer Captain George Waymouth brought his ship,Archangel, into Pentecost Harbor (Maine), near the St. George River in 1605, where he recorded having “found notable high timber trees, (that would make) masts for ships of four hundred tons.” Twenty years following the Pilgrim’s landing at Plymouth Rock, “Masting” became New England’s first major industry as Eastern White Pine quickly became a popular item for export to shipbuilding ports in the Caribbean, England, and as far away as Madagascar.

A “mast” pine several hundred years old, 5 feet in diameter at the butt and 120 feet in length might weigh 10 tons. Special, extra-long decks had to be added to existing ships to accommodate the Eastern White Pine mast materials. Of all the species of wood used for masts around the world, these were the lightest in weight and the largest in size. Other critical shipbuilding components such as frames, planking and knees, pitch and tar for seaming, resins and turpentine for paint and varnish, and spars to hold sails aloft were produced from the wood. Mast production was connected to the existing lumber production and led to the development of markets and channels of distribution for those products, as well.

To maintain its world dominance of the seas, Great Britain needed the strongest and fastest ships and Eastern White Pine would make these ships the greyhounds of their day and a force to reckon with in any battle. England’s forests had been cut for firewood in the Middle Ages, and by the 17th century, the closest supply for mast timbers was in the Baltic, where they competed with the French, Spanish, and Dutch for the great Baltic firs. Securing a shipbuilding material resource all to itself became paramount to the King and the Royal Navy, and the knowledge that the New England colonists were harvesting the largest of the Eastern White Pine’s at an unknown rate led to future supply concerns.

To maintain its world dominance of the seas, Great Britain needed the strongest and fastest ships and Eastern White Pine would make these ships the greyhounds of their day and a force to reckon with in any battle. England’s forests had been cut for firewood in the Middle Ages, and by the 17th century, the closest supply for mast timbers was in the Baltic, where they competed with the French, Spanish, and Dutch for the great Baltic firs. Securing a shipbuilding material resource all to itself became paramount to the King and the Royal Navy, and the knowledge that the New England colonists were harvesting the largest of the Eastern White Pine’s at an unknown rate led to future supply concerns.

Acting as dominion over the forests of “New England”, the King assumed ownership of the best of the Eastern White Pine trees and appointed a legion of Surveyors of Pines and Timber to survey the forestland “within 10 miles of any navigable waterway” and mark all suitable trees with “The King’s Broad Arrow”, a series of three hatchet slashes. This was the symbol commonly used to signify ownership of property or goods by the Crown, in this case to be owned and used solely by the Royal Navy. Any tree of a diameter of twenty-four inches and greater at twelve inches from the ground, with “a yard of height for each inch of diameter at the butt” was blazed with the broad arrow. Violation by the colonists of this rule would be assessed a fine of £100. Persons appointed to the position of Surveyor-General of His Majesty’s Woods were responsible for selecting, marking and recording trees as well as policing and enforcing the unlicensed cutting of protected trees.

any navigable waterway” and mark all suitable trees with “The King’s Broad Arrow”, a series of three hatchet slashes. This was the symbol commonly used to signify ownership of property or goods by the Crown, in this case to be owned and used solely by the Royal Navy. Any tree of a diameter of twenty-four inches and greater at twelve inches from the ground, with “a yard of height for each inch of diameter at the butt” was blazed with the broad arrow. Violation by the colonists of this rule would be assessed a fine of £100. Persons appointed to the position of Surveyor-General of His Majesty’s Woods were responsible for selecting, marking and recording trees as well as policing and enforcing the unlicensed cutting of protected trees.

Use of the broad arrow mark commenced in earnest in 1691 when the revised Massachusetts Bay Charter included in its last paragraph a “Mast Preservation Clause” stating (original language):

“And lastly for the better provideing and furnishing of Masts for Our Royall Navy Wee doe hereby reserve to Vs Our Heires and Successors all Trees of the Diameter of Twenty Four Inches and upwards of Twelve Inches from the ground growing vpon any soyle or Tract of Land within Our said Province or Territory not heretofore granted to any private persons And Wee doe restrains and forbid all persons whatsoever from felling cutting or destroying any such Trees without the Royall Lycence of Vs Our Heires and Successors first had and obteyned vpon penalty of Forfeiting One Hundred Pounds sterling vnto Ous Our Heires and Successors for every such Tree soe felled cult or destroyed without such Lycence had and obteyned in that behalfe any thing in.”

The colonists paid little attention to this edict and tree harvesting increased with disregard for broad arrow protected trees. However, as Baltic imports decreased, the British timber trade increasingly depended on North American trees, and enforcement of the Broad Arrow policies increased. Subsequent British Parliament Acts of 1711, 1722 and 1772 extended protection, finally to 12 inch diameter trees.

The growing enforcement and stricter criteria of the decree angered the colonists who made their livelihood from the Eastern White Pine wood products they produced and sold. The early American pioneers had this timber on their properties, within their grasp, yet they were not to touch it.

The growing resentment led to “Swamp Law” whereby many of the “King’s” pines were cut illegally, the “Kings Broad Arrow” mark obliterated and the wood was put to use. Others cut down and used all the trees marked with the king’s broad arrow and then placed the broad arrow on smaller trees. Many of the marked “Mast” trees were partially burned in mysterious fires or splintered in unusual gales.

This rebellion led to numerous skirmishes throughout New England between local settlers and British authorities, with these clashes appropriately given names such as “The White Pine War” and “The Pine Tree Riot”.

This rebellion led to numerous skirmishes throughout New England between local settlers and British authorities, with these clashes appropriately given names such as “The White Pine War” and “The Pine Tree Riot”.

The Revolutionary War was about many things, and Eastern White Pine weighed heavy on the minds and hearts of the colonists desire for independence. Some historians believe that denial of use of these trees was at least as instrumental as taxation of tea in bringing about the American Revolution and the first acts of rebellion against British rule. In fact, the Eastern White Pine was the emblem emblazoned on the first colonial flag, including one bearing a white pine purportedly flown at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

at least as instrumental as taxation of tea in bringing about the American Revolution and the first acts of rebellion against British rule. In fact, the Eastern White Pine was the emblem emblazoned on the first colonial flag, including one bearing a white pine purportedly flown at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

This species truly shaped early America.