The colonial architecture of Providence, Rhode Island, may not be as renowned as that of Salem or Portsmouth, but it’s just as historically important, with seaside dwellings dating to the beginning of the eighteenth century. Written in 1918, Volume IV, Issue III of the historic White Pine Architectural Monographs highlights some of the most important structures that survived into the twentieth century.

One example is the Christopher Arnold House, built about 1735, which features the oldest doorway in Providence with carvings that were likely inspired by those on even older furniture. Likewise, the Crawford House has “a very remarkable door with large, bent-over leaves above the caps of its pilasters, and the curious bending up of the back band in the middle of the lintel… doors like this are rare.”

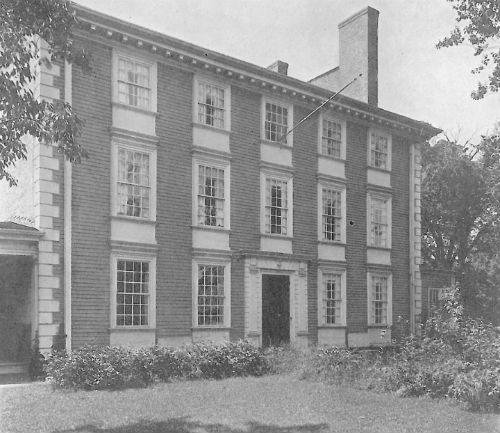

“The second quarter of the century, especially the years just before 1750, and, of course, even more the years just before the Revolution, when the money from privateering in the Old French War was flowing into the town, saw the rise and spread here, as in the rest of New England, of the central-entry type of plan – that in which a long hall runs through the back, with two rooms on each side.”

“Most of the houses of this kind in Providence are of brick; thew olden house of early date on that plan is not common. At any rate, it has not survived in any numbers. It is to be seen it its glory for Rhode Island, in Newport and not in Providence.” Moving into the nineteenth century, after a period of construction inactivity during the Revolution, three-storied wooden mansions began to spring up. Read more at the White Pine Monograph Library.