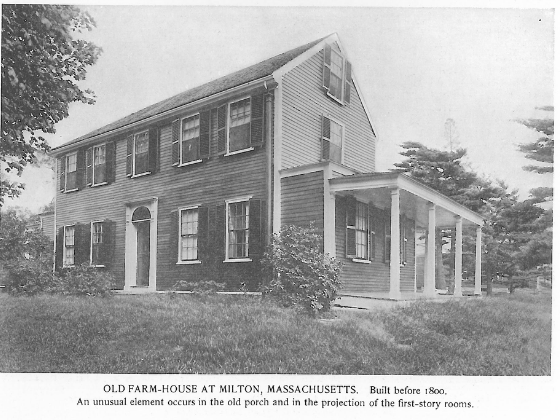

An important stop along the development of New England’s colonial architecture, simple farmhouses of the early to mid 18th Century shed some of the compulsory Gothic trappings carried overseas to the first English American settlements for a more streamlined, humble, fuss-free appearance. The second edition of the White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs ever to be published, written in April 1916, catalogues notable examples across Massachusetts as they stood over a century ago. Some of these homes are still incredibly well-preserved today, including Dalton House, pictured above in recent years and below in the early 20th century.

These dwellings had uncomplicated pitch or gambrel roofs and were typically one room deep and two stories high, built with one ridge pole and two end gables. In later years, as settlers grew more prosperous, the homes were often altered or expanded, with ‘service ells’ added to the rear or side, or the houses were doubled, with an identical-plan addition set right behind the first.

The General Putnam House in Danvers, Massachusetts, built around 1744, is an example of a gambrel-style colonial home with a service ell added in the rear. Says the writer of this monograph, “This house presents as much of a contrast as is possible to the Dalton House at Newburyport. While variously dated as being from 1750 to 1760, the photograph of this house speaks for itself, presenting an unusually spacious and generous treatment of the gambrel roof slope (now slated, while the house has a new end bay and suspiciously widely spaced columns at the entrance!) The whole design nevertheless shows much more refinement of handling than is apparent in the other example mentioned.”

Built in 1720, the Dalton House is generally held to be an example of “a plain house of the purest colonial type,” yet it was a mansion in its time (and many of us would still consider it one today.) Visits from George Washington, President Monroe, Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams and John Hancock are among the reasons it’s considered an architectural and historical treasure. Having always been occupied by wealthy people since it was built, it has never deteriorated, and its porch is a particularly fine example of colonial woodworking.